AN04a3_Ch.16: Peoples and Empires in the Americas: Mexica Control Central Mexico

Timeline: 8th C. BCE – 16th C.

FQ: How did the Mexica (Aztecs) build and maintain a fast-growing empire engulfing central Mexico?

Main Idea: Through alliances and conquest, the Mexica created a powerful empire in Central Mexico. Previously held ideas about the Mexica having an “Old World” style empire have had to be modified. This civilization had much to distinguish itself from Europeans and Mesoamericans alike.

CCSS/ NYSS…

I. Vocabulary: Please refer to the Crossword Puzzle

A. Aztec: This name is derived from the mythical homeland of the Nahua-speaking peoples, Aztlán. All Nahua-speaking peoples of the Central Mexican valley were technically ‘Aztec’. However, the specific subgroup of Nahua-speaking people that dominated the valley prior to the Encounter were called Mexica. Their ancestral land is believed to have been northwest of current-day Mexico City, not far south from the current U.S. – Mexico border.

B. Nahuatl: Oral language of the Mexica. Spoken among a very small segment of the Mexican population today. A noticeable characteristic of this language is the pairing of the ‘T’ and ‘L’ sounds (Ex. Tenochti”tl”án, Nahua”tl” and “Tl”atoani)

II. Mexica

A. Context

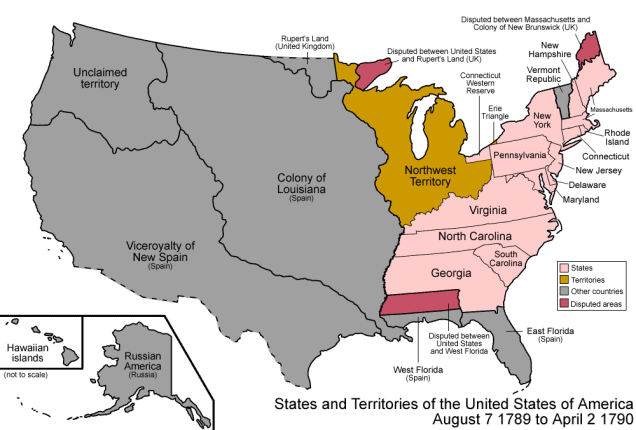

1. Time: ~1160 – 1519 (1)

2. Place

a. Land of origin was Northwest Mexico.

b. Migrate to Central Mexican Valley (Mythical/ Historical Reasons).

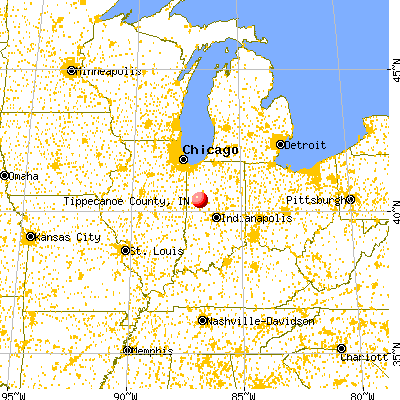

c. Lake Texcoco: The lake which becomes home for the Mexica. Once located where Mexico city now exists. The largest island in this lake becomes Tenochtitlán (City of the Tenochs)- capital of the Mexica.

3. Circumstance

a. Originally Nomadic, the Mexica become sedentary when they settle in the central Mexican valley.

b. Continual conflict with neighboring peoples=> When the Mexica settle Tenochtitlán, they become ‘soldiers for hire’ (Mercenaries) for the peoples living along the lake’s basin. In return for their services, the Mexica receive compensation.

B. Political

1. Conquest & Triple Alliance: The Mexica became the dominant partner in an alliance with two other lakeside peoples. Together, the alliance partners expanded and then maintained rule over a million subjects.

2. Tlatoani: A title meaning Speaker. This title was conferred on individuals with communal leadership roles or the ‘administrative head’ of the alliance. Once Tenochtitlán became the empire’s principal city, its ruler became the undisputed sovereign of the entire empire. He was simultaneously the empire’s administrative, military, and religious leader. Since the Mexica were the dominant member of the alliance, the Tlatoani was chosen from among the Mexica nobility.

3. Tribute System: Subject peoples of the Triple Alliance would offer tribute on a regular basis. Tributary status could also be conferred on non-subject peoples who wish to maintain peaceful relations with the Mexica-led alliance. The form of the tribute was always the same=> a valuable manufactured or natural product: Woven cotton cloth, Quetzal Feather Cloak, and Obsidian tools; Cacao beans, Corn, Quetzal feathers, and Obsidian.

C. Social

1. Mexica Family: The base family unit consisted of two parents and their unmarried children. The main function of parents was the education of the children and food preparation.

2. Calpulli: While extended families farmed the land, they usually did not own it. They were allowed to use it by the calpulli to which they belonged. Calpulli were groups of families that controlled the use of the land and performed other functions.

In urban areas the wisest and most powerful leaders of each calpulli constituted a city council. These leaders in turn selected four main members. One of these prime members was selected to be the tlatoani of the city.

3. Social Hierarchy

The Mexica condoned slavery as a punishment for severe crimes, but even slaves had some rights. For one, their families and offspring remained free. In addition, if a slave found time to do other work on the side, freedom could be bought for a price. Nobles were not exempted from slavery. In fact, nobles were held to an even higher standard than the commoners. Nobles were expected to provide a good example for the rest of the empire’s subjects. On the other hand, good deeds such as valor in battle were rewarded, and many soldiers who proved themselves in battle were admitted into one of the privileged military orders. Every citizen of the empire belonged to a class from birth, it was possible to change one’s place in society.

D. Religious

1. Deities

a. Quetzalcoatl: Feathered Serpent- Represented as Corn, Creator, Knowledge

b. Huitzilopochtli: Sun, War, Hummingbird. It was the patron deity.

c. Tlaloc: Rain

2. Rituals: The Mexica worshiped numerous of gods and goddesses. They were predominantly agricultural gods because Mexica culture was based heavily on farming. Many rituals of worship were aimed at appeasing the gods. Rituals were determined by season or circumstance. (2)

a. Sacrifices: Can be of a personal or public nature. The most important rituals would involve the ‘letting’ of blood. (3)

– Personal/ Private Sacrifice Ritual

– Public Sacrifice Ritual (Scheduled and Unscheduled): Often performed on the Great Pyramid (Templo Mayor)

– Annual Sacrifice

b. The most important structure in the capital’s main plaza was a large, terraced pyramid crowned with two stone temples dedicated to the most important Mexica gods—the sun god (also the god of war) and the rain god.

c. The Calendar Stone

One of the most famous surviving Mexica sculptures is the so-called Calendar Stone. It weighs 22 metric tons and measures 3.7 m (12 ft) in diameter. The calendar stone represents the Mexica universe.

E. Achievements and Contributions

1. Tenochtitlán (Mexica Capital)

Tenochtitlán is the 2nd largest city (pop.) on Earth by 16th C. It was the center of the Mexica world. The marvels of the island city were described at length by the Spanish conquistadores, who called it the “Venice of the New World” because of its many canals. At its height, the city had a population of more than 200,000, according to modern estimates, making it one of the most populous cities in the pre-modern world.

Tenochtitlán was connected to the mainland by three well-traveled causeways, or raised roads. During the rainy season, when the lake waters rose, the causeways served as protective dikes. Stone aqueducts brought fresh drinking water into the city from the mainland. The city’s canals served as thoroughfares and were often crowded with canoes made from hollowed logs. The canoes were used to carry produce to the public market in the city’s main plaza.

At the center of Tenochtitlán was a ceremonial plaza paved with stone. The plaza housed several large government buildings and the palace of the Mexica ruler, which was two stories high and contained hundreds of rooms.

2. Templo Mayor (Main Temple)

3. Technology

a. Canal Network

b. Chinampas: Farming provided the basis of the Mexica economy (as with most civilized societies). Their most important agricultural technique was the reclamation of swampy land by creating chinampas, or artificial islands that are known popularly as “floating gardens.” To make the chinampas, the Mexica dug canals through the marshy shores and islands, then heaped the mud on huge mats made of woven reeds. They anchored the mats by tying them to posts driven into the lake bed and planting trees at their corners that took root and secured the islands permanently. On these fertile islands they grew corn, squash, vegetables, and flowers.

4. Agricultural

a. Mexica farmers cultivated corn (Maize) as their principal crop. From the corn meal, the Mexica made flat corn cakes called tortillas, which was their principal food.

Other crops included: beans, squash, chili peppers, avocados, tomatoes (Tomatl), and chocolate (Xocolatl). The Mexica raised turkeys and dogs, which were eaten by the wealthy; they also raised ducks, geese, and quail.

b. Mexica farmers had many uses for the maguey plant (also known as the agave), which grew to enormous size in the wild. The sap was used to make a beer-like drink called pulque, the thorns served as needles, the leaves were used as thatch for the construction of dwellings, and the fibers were twisted into rope or woven into cloth.

III. Summary: Why it matters now.

This time period saw the origins of one of the 20th century’s most populous cities, Mexico City.

Resources:

– Slide Presentation

– Credit to the following (former) students for gathering data incorporated into this lesson: Jimmy Wang, Kevin Teoh, and Nandita Garud from May 2001

– World History: Patterns of Interaction

– Film: CNN’s Millennium Series.

– Marrin, Albert. Mexicas and Spaniards: Cortes and the Conquest of Mexico. New York: Atheneum, 1986.

– Clendenin, Inga. Aztec.

– Chronicles of Hernan Cortes and Bernal Diaz.

Footnotes

(1) The civilization had not yet reached its height when Hernan Cortes arrives in 1519.

(2) The last five days of solar calendar were days of bad omens; Some rituals involved drinking of pulque and burial of warriors.

(3) Blood is the essence of life. It was the most sacred and valuable of human possessions.